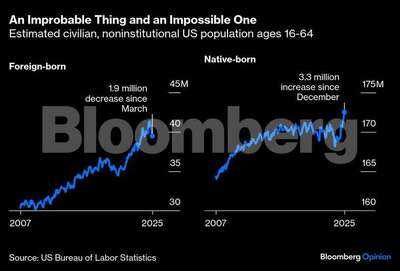

Something remarkable has been going on lately with the population estimates maintained by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. They show a decline of 1.9 million in the foreign-born working-age population in the US (defined here as ages 16 through 64) since March and an increase of 3.3 million in the native-born working-age population since December.

The foreign-born working-age population may well be shrinking. The flow of illegal immigration across the Mexican border slowed sharply last year and has ground almost to a halt this year, and since January the Trump administration has been narrowing legal immigration channels, canceling temporary legal immigration programs and increasing the pace of deportations for those here illegally. It’s extremely unlikely that 1.9 million people ages 16 through 64 have left the country since March, but the direction at least could be correct.

Such an increase in the native-born working-age population, on the other hand, is impossible. Changes in that population are quite easy to predict, given that we know how many people were born in the US 16 to 64 years ago and how many have died since — and, while there admittedly aren’t great recent statistics on this, the number of native-born Americans who leave the country permanently is most likely small. Just going by births, the 16-to-64 US population is due for six consecutive years of declines from this year through 2030.

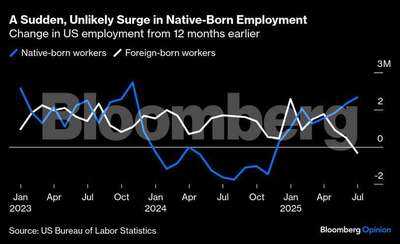

All this is context for understanding the 2.5 million job increase in native-born employment since December that the BLS is also reporting. Given that it came after a year of foreign-born workers seemingly driving all US employment gains, it is understandably being greeted by Trump administration officials (and would-be Trump BLS chief E.J. Antoni) as evidence of a remarkable turnaround wrought by Trump’s economic policies. As you can probably already tell from the population data I’ve cited, it’s not that. But what is it, exactly?

The big changes in population and employment are artifacts of how the BLS estimates population for the purposes of calculating the labor-force statistics it derives from the Census Bureau’s monthly Current Population Survey, the so-called household survey. The priority is generating accurate percentage indicators such as the unemployment rate, labor-force participation rate and employment-population ratio, not reliable time series of the levels of employment or population.

The big changes in population and employment are artifacts of how the BLS estimates population for the purposes of calculating the labor-force statistics it derives from the Census Bureau’s monthly Current Population Survey, the so-called household survey. The priority is generating accurate percentage indicators such as the unemployment rate, labor-force participation rate and employment-population ratio, not reliable time series of the levels of employment or population.

The establishment survey — aka Current Employment Statistics — that is the other contributor to the monthly BLS employment report is aimed at generating accurate estimates of the level of nonfarm payroll employment and is revised repeatedly as late responses come in and then a backup set of statistics based on state unemployment insurance records is released. A big downward revision in past months’ payroll jobs totals in the employment report released early this month led Trump to fire the director of the BLS and nominate Antoni, a Heritage Foundation economist with a reputation for sloppy, partisan work, as the agency’s new chief.

The employment indicators from the household survey aren’t subsequently revised, but every January the BLS does adjust its population numbers to align them with the latest population estimates from the Census Bureau. This December, the Census Bureau revised its national population estimates upward to better reflect the big wave in immigration from mid-2021 to mid-2024, estimating net immigration of 2.8 million people from mid-2023 to mid-2024, and increasing its estimate of 2021-2023 net immigration from 2.1 million to 4 million. This and other changes in the 2024 population estimates led the BLS to report a 3 million increase from December to January in the 16-and-older civilian, noninstitutional US population, with the gains split roughly evenly between native-born and foreign-born. Again, this wasn’t because anybody at BLS thought the US 16-and-older population actually grew that much from December to January, just that the new population estimates were higher than the previous ones, and it doesn’t revise earlier estimates. (For a more detailed explanation, I recommend this piece by Jed Kolko, who as undersecretary of commerce for economic affairs in the Biden administration oversaw the Census Bureau.)

The Census Bureau also makes forward-looking monthly population estimates once a year based on anticipated deaths, 16th birthdays and immigration trends, which the BLS uses to produce its monthly population totals until the next annual update. The monthly BLS estimates of changes in the native-born and foreign-born population and workforce, though, are based on what people say in the monthly household surveys. Since Donald Trump became president, foreign-born residents of the US appear to have become much less likely to respond to the surveys or tell survey takers they weren’t born in the US. Because the overall monthly population numbers are on autopilot, this has resulted in declining foreign-born population and employment numbers and increasing native-born numbers.

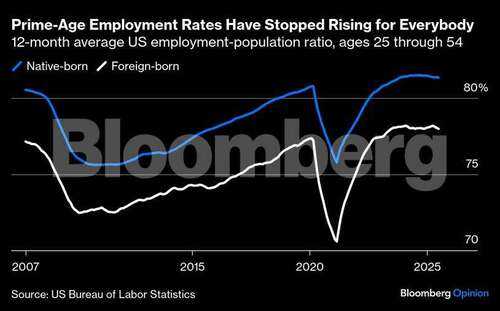

If native-born workers were in fact making big employment gains now, these would show up in their ratio of employment to population, which is best measured for so-called prime-age workers 25 to 54 so as not to be skewed by the aging of the population. Prime-age employment-to-population numbers for native- and foreign-born workers are not available in seasonally adjusted form and thus jump around a lot from month to month, so I’ve taken annual averages, which indicate that both native-born and foreign-born employment rates are flat and possibly beginning to trend downward.

President Trump’s immigration crackdown is to some extent based on the theory that it will improve job prospects for native-born workers by removing foreign-born competitors. Because immigration is the only possible source of growth in the US working-age population for the rest of this decade, though, stopping or reversing its flow will also make it hard to achieve much of any economic growth. So far, in any case, the net result for native-born workers appears to be no improvement at all.

President Trump’s immigration crackdown is to some extent based on the theory that it will improve job prospects for native-born workers by removing foreign-born competitors. Because immigration is the only possible source of growth in the US working-age population for the rest of this decade, though, stopping or reversing its flow will also make it hard to achieve much of any economic growth. So far, in any case, the net result for native-born workers appears to be no improvement at all.

The foreign-born working-age population may well be shrinking. The flow of illegal immigration across the Mexican border slowed sharply last year and has ground almost to a halt this year, and since January the Trump administration has been narrowing legal immigration channels, canceling temporary legal immigration programs and increasing the pace of deportations for those here illegally. It’s extremely unlikely that 1.9 million people ages 16 through 64 have left the country since March, but the direction at least could be correct.

Such an increase in the native-born working-age population, on the other hand, is impossible. Changes in that population are quite easy to predict, given that we know how many people were born in the US 16 to 64 years ago and how many have died since — and, while there admittedly aren’t great recent statistics on this, the number of native-born Americans who leave the country permanently is most likely small. Just going by births, the 16-to-64 US population is due for six consecutive years of declines from this year through 2030.

All this is context for understanding the 2.5 million job increase in native-born employment since December that the BLS is also reporting. Given that it came after a year of foreign-born workers seemingly driving all US employment gains, it is understandably being greeted by Trump administration officials (and would-be Trump BLS chief E.J. Antoni) as evidence of a remarkable turnaround wrought by Trump’s economic policies. As you can probably already tell from the population data I’ve cited, it’s not that. But what is it, exactly?

The establishment survey — aka Current Employment Statistics — that is the other contributor to the monthly BLS employment report is aimed at generating accurate estimates of the level of nonfarm payroll employment and is revised repeatedly as late responses come in and then a backup set of statistics based on state unemployment insurance records is released. A big downward revision in past months’ payroll jobs totals in the employment report released early this month led Trump to fire the director of the BLS and nominate Antoni, a Heritage Foundation economist with a reputation for sloppy, partisan work, as the agency’s new chief.

The employment indicators from the household survey aren’t subsequently revised, but every January the BLS does adjust its population numbers to align them with the latest population estimates from the Census Bureau. This December, the Census Bureau revised its national population estimates upward to better reflect the big wave in immigration from mid-2021 to mid-2024, estimating net immigration of 2.8 million people from mid-2023 to mid-2024, and increasing its estimate of 2021-2023 net immigration from 2.1 million to 4 million. This and other changes in the 2024 population estimates led the BLS to report a 3 million increase from December to January in the 16-and-older civilian, noninstitutional US population, with the gains split roughly evenly between native-born and foreign-born. Again, this wasn’t because anybody at BLS thought the US 16-and-older population actually grew that much from December to January, just that the new population estimates were higher than the previous ones, and it doesn’t revise earlier estimates. (For a more detailed explanation, I recommend this piece by Jed Kolko, who as undersecretary of commerce for economic affairs in the Biden administration oversaw the Census Bureau.)

The Census Bureau also makes forward-looking monthly population estimates once a year based on anticipated deaths, 16th birthdays and immigration trends, which the BLS uses to produce its monthly population totals until the next annual update. The monthly BLS estimates of changes in the native-born and foreign-born population and workforce, though, are based on what people say in the monthly household surveys. Since Donald Trump became president, foreign-born residents of the US appear to have become much less likely to respond to the surveys or tell survey takers they weren’t born in the US. Because the overall monthly population numbers are on autopilot, this has resulted in declining foreign-born population and employment numbers and increasing native-born numbers.

If native-born workers were in fact making big employment gains now, these would show up in their ratio of employment to population, which is best measured for so-called prime-age workers 25 to 54 so as not to be skewed by the aging of the population. Prime-age employment-to-population numbers for native- and foreign-born workers are not available in seasonally adjusted form and thus jump around a lot from month to month, so I’ve taken annual averages, which indicate that both native-born and foreign-born employment rates are flat and possibly beginning to trend downward.

You may also like

Nigeria mosque attack: At least 50 killed; gunmen strike during prayers

Novak Djokovic 'targeted by Serbian government and considers fleeing to Greece'

Malwa Mill-Patnipura Bridge To Be Ready Before Dussehra, Says Mayor Pushyamitra Bhargav

UP Urea Smuggled To Nepal, Sold At Exorbitant Rates

Celebs Go Dating's Liv Hawkins reveals unaired Louis scene before 'vulnerable' moment